In my individual intervention into the public space of a small downtown park in Greensboro, North Carolina (photo 1), I set up a poster saying “Free Poetry” with a pink balloon attached (photos 2 & 3)

and arranged sets of poems printed on colored construction paper on a wooden seating area. I chose poems for adults and children by racially and ethnically diverse poets, Juan Felipe Herrera, Mary Oliver, Langston Hughes, Maya Angelou, Lucille Clifton, Claudia Rankine, Shel Silverstein, Robert Frost, and William Blake.

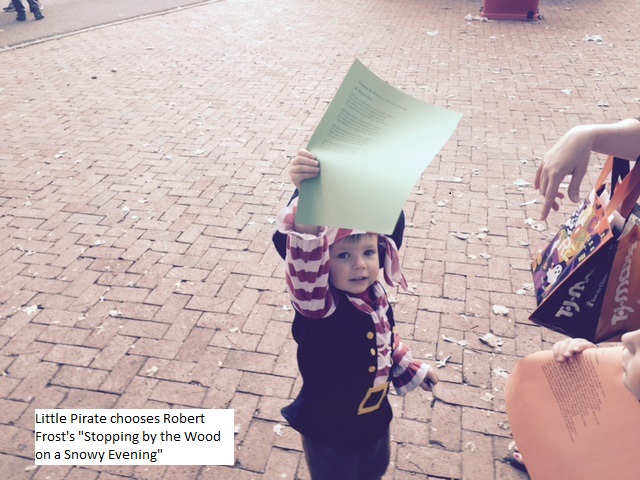

A white father dressed as superman and his costumed children were the first to take poems (photo 4), followed by two siblings dressed as pirates (photos 5 & 6).

A white father dressed as superman and his costumed children were the first to take poems (photo 4), followed by two siblings dressed as pirates (photos 5 & 6).

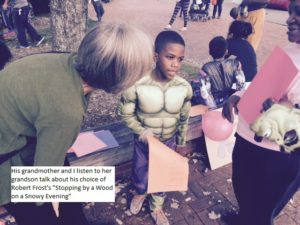

As her grandson read over the poems to decide which one to take, an African American woman about my age said she couldn’t read without her glasses, and so I read her Lucille Clifton’s poem, with the last line, “come celebrate with me that everyday something has tried to kill me and has failed.” She said, “I like that poem, I’ll take that” (photos 7 & 8).

A family who I overheard speaking Spanish, had been eyeing the poems from afar, but hadn’t come closer to read any of them. I told them that one of the poets was Juan Felipe Herrera, the new poet laureate of the US, and that he had migrated to California from Mexico when he was a child. The mother said to her son, “Did you hear that? He’s from Mexico and California!” She nudged her son, who said he was in the fourth grade, to read it. In a soft voice, he read the poem “Let Me Tell You What a Poem Brings” (photo 9).

The last poem I gave away was a balloon. A little white girl, about 5, in a pink t-shirt and shorts asked if she could have the pink balloon attached to the Free Poetry sign (Photo 10).

My favorite part of the poetry give away was being near children as they read the poems, close enough to feel their breath as they read, seeing the pride of those who read aloud. I was struck by how many people were drawn to the poems, and that some were surprised that they could take them with them, that they were free.

Giving out poems was my third choice of interventions. I’d thought of collecting donations for a bank in a wealthy neighborhood, or donations for anti-racism training in a white upper middle class neighborhood, but ran into barriers; upper middle class and wealthy whites gather in heavily-controlled private spaces, such as country clubs and upscale grocery stores that would never have let me ask for donations. I considered going to one of the local parks, but there’s an ordinance for the entire city that makes asking for money illegal unless you have a permit.

As I realized how constrained I was by city rules and regulations, I felt very un-free—a powerful lesson in the politics of space.

Being so close to a Halloween Fair with a haunted house, and various booths with activities and food, lessened the strangeness of my giving out free poetry. As such, the displacement was mild, gentle, and apolitical.

My project was an example of an individual’s intervention in public space, and ephemeral public art. The project was a displacement of the activity of reading poetry–which usually takes place in a library, book store, at home, or in cultural and educational institutions—to a public park. The project defied market culture in that I gave away poems instead of selling them. The space was racialized, in that people at the free Halloween Fair appeared to be mostly middle and working class, and people of color. They were receptive to a white woman with greying hair giving them free poetry, including several poems that touched on race and class.

The political nature of the project was severely constrained by the city’s rules and regulations about public activities, including art, and by the privatization of communal space for wealthier whites. I was reminded of the cage that Maria Galindo wore in her presentation at the Creative Time Summit at the Venice Biennale. I felt very constrained, not free at all in my city; the cage I’m in prevented me from asking for donations for a bank, or for anti-racism training in a white neighborhood, which would stir up considerably more discomfort and disorientation than giving away poetry did.

Photos: Glenn M. Hudak