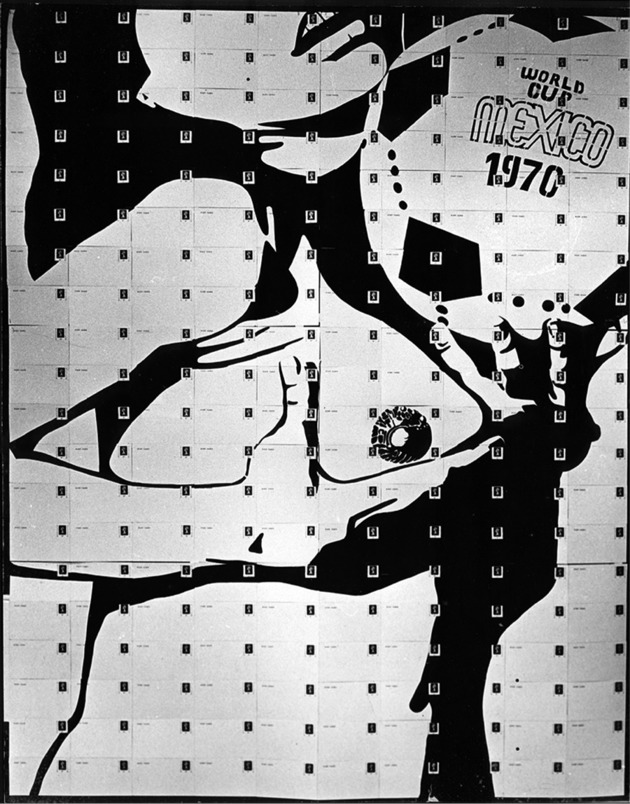

The Mail Art movement is one example of the successful inversion of an existing system – using the mail to assemble often forbidden artworks in a new artwork. One artist that immediately came to mind was Felipe Ehrenberg, and his work Ariiba Y Adelante. This black and white illustration shows a sexualized image of a woman holding a “Mexico World Cup 1970” football in one hand, and her breast in the other. The work is made up of 200 stamped postcards, which Ehrenburg painted a part of the overall image on, so that when reassembled in the correct order, the larger image became visible. The image came from a series of photographs published in England that were released at the time of Mexico’s hosting of the Wolrd Cup. Ehrenburg mailed the 200 post cards on November 15 1970 from three separate post offices in London, sending all to the Mexican Independent Salon in preparation for showing at its third exhibition.

Response and reaction to existing structures and institutions is a key part of this work, in many different ways. Firstly, there is Ehrenburg’s own displacement and location in London. After the Tlateloclco massacre in 1968, Ehbrenberg decided to leave the country with his family, and move to England to escape the violence that the state was responsible for. By using the mail system, Ehrenburg shows the capacity of systems to be used to overrun existing institutions or other systems – in this case, the system of mail trumps the system of governmental oppression, or the government in itself.

Ariiba Y Adelante is also a reaction to the laws and restrictions of the system, as the Mexico Mail Service refused to carry any pornographic images.

Lastly, the work reacts to the systems used by art institution in both its means of transportation and its methods of assembly. Typically, the transportation and handling of art is treated with great care and is the most costly part of any exhibition, and is only undertaken by experts. Ehrenburg used the standard post service to process the cards, and gave instructions for the work to be mounted on a crimson background, which would serve to highlight the error of the postal system if any cards did not show up. Upon their arrival at the gallery, his instructions were “During the opening night of the Third Annual Exhibition of the Independent Salon, and after a respectable amount of citizens are gathered, my duly appointed representative shall begin by tacking up each card in order. . . . Members of the public are happily invited to help.” Not only were they sent through a system accessible to anyone, they were assembled by anyone. The reliance upon many highlights the collaboration necessary for the work’s success, and the social engagement that Ehrenburg made so inherent at all stages of Ariiba Y Adelante’s production.